Moths have always been my main interest so far as the hours of darkness are concerned, but we have another little creature in the UK which matches them for interest and delight. Behold the shining lights of some of our local glowworms, that amazing variety of beetle which seems unbelievably exotic amid our green - and often damp - fields.

Like many people, I suspect, I have always had the vague idea that glowworms are rare and predominantly found in the South or South West. The only time I have previously seen them was in Cornwall long ago. The work of the National Glowworm Survey run voluntarily and with great enthusiasm since 1990 by Robin Scagell and friends has transformed the picture. As their excellent website explains, there were thought to be fewer than a hundred glowworm sites in the UK when the survey started. Since then, hundreds more have been discovered and new ones are mapped every year.

I had no idea that we had them near our house until a friend who lives a couple of miles away posted some pictures of their colony on the local Facebook group. We decided to have a look for ourselves in nearby fields with a couple of younger and sharper-eyed friends. This promptly revealed one of the main reasons why British glowworms' lights have been hidden under bushels: it requires willpower to haul yourself out of the armchair and head outside at 10.45pm. But you need the dark to spot the little beetles' lights, so we managed to jump this first hurdle and off we went.

The first field we checked out was barren and the second strip of grass alongside a copse was also dark. But we were happy chattering away and had gone in the right frame of mind - not really expecting success. Then one of our friends tugged her partner's sleeve and said: "Look there!" And down at the base of a clump of long grass, appearing to flicker as the stems waved about in a gently breeze, was a small but extremely bright light.

The first field we checked out was barren and the second strip of grass alongside a copse was also dark. But we were happy chattering away and had gone in the right frame of mind - not really expecting success. Then one of our friends tugged her partner's sleeve and said: "Look there!" And down at the base of a clump of long grass, appearing to flicker as the stems waved about in a gently breeze, was a small but extremely bright light.We found three more in the next 20 minutes, all females glowing from two of their lower abdominal segments in the hope of attracting a nearby male. The latter also glow but not so strongly and less often while the larvae can only manage to 'twinkle briefly', in the Glowworm.org.uk website's endearing phrase. So it's the females that you are likely to see - and from quite a distance. Penny spotted our fourth from at least 30 yards away. The website has copious advice and lots of terrific information and here's one of its maps with masses of dots where glowworms had been found up to 2006. If you have the energy and follow their advice on where to look, you have a good chance of enjoying a new Summer night-time experience. Leave them where they are, or their numbers may dwindle.

The light itself is caused by an enzyme oxydising a molecule, a process known as bioluminescence whose possible commercial and practical applications for humanity are the subject of much study. It is even possible in theory that self-illuminating trees could do the work of streetlamps but concerns about genetic modification have slowed progress. Meanwhile, don't you like the beetle's Linnean name Lampyris noctiluca which means Shining One (in classical Greek) Night Light (in Latin) What fun the old namers had! It isn't a worm either, but that was the standard term for most things insect-like until the 18th century.

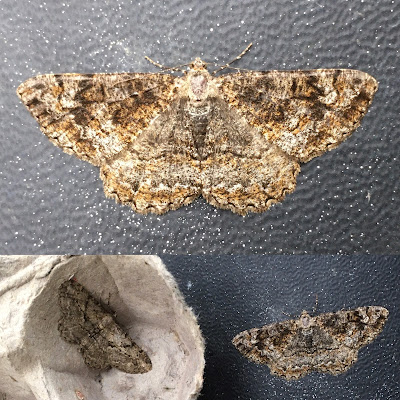

I am sorry that my night photos are not better but, as you may imagine, this was an extreme challenge for my iPhone. They give a correct impression, however, of the pattern of the lights - two bands and two dots - and here are a couple more which show one of the beetles with the help of flash. Goodness knows what the poor thing thought was happening but it kept its light on.

Since I'm straying from moths, I'll include a few other interesting encounters away from my usual subject, firstly a fine stag beetle which a Grandpa like myself was showing to his grandchildren by the Thames where we went for a swim on the hottest of last week's days. Then a Bee Orchid, the sixth species we've found here which probably completes our tally, and a Red Admiral which took an interest in my shoes. The Admirals seem to have hatched a little earlier than usual this Summer, perhaps because of the long run of good weather.

Finally, my lawn-mowing yesterday disturbed this fine, plump grass snake in one of those coincidences which so fascinated the writer Arthur Koestler. Only an hour before, I had put the finishing touches to a set of serpentine roof struts which I have whittled for the grandchildren's treehouse.